Published in The Climber, Jan 2019

Words and photos by Derek Cheng

A wise person once told me that the key to a climbing destination was to have your rest days almost as fun as your climbing days.

I had no option but to test this when my time in Kalymnos, the sport-climbing Mecca of Greece, was forced to include a sabbatical after a tufa broke while I was clipping the third bolt of a climb. The huge amount of slack in my hand led to a half-caught ground fall, but the real rub was that the tufa, about the size of half my torso, landed on top of my ankle.

This was actually entirely the fault of my own poor judgement. I had chosen the path of least resistance by bypassing the normal starting sequence. The tufa that broke was admittedly a tad hollow, dirty, and not made of the most solid limestone, which, in Kalymnos, there is no shortage of.

I scootered off to the hospital in the main centre of Pothia to see if the rather languid pace of island life was in any way indicative of the quality of medical services. It was a Friday afternoon. I circumnavigated the building and found nothing resembling an entrance. There was no sign, or anything to suggest that the place was in use.

I eventually had to accost a local who was standing outside while waiting for his wife to be treated. He ducked inside to let someone know that there was a visitor who—it shouldn’t come as a surprise—was seeking medical attention.

Eventually, a phone call had to be placed to summon the radiologist, who had gone home for the day. She returned to x-ray me—free of charge—and after being bandaged up and told I had no broken bones, I exited with my swollen ankle enlarging by the hour.

So began my two-week recovery period, which may have been challenging had I not been on a sun-soaked island in Greece. Recliners on the beach, and ocean swims. Darting around curving mountain roads on a scooter, wind in my beaming face. Sampling the local cheeses, figs and olives at the market. Getting increasingly sunburnt on our grotesquely large balcony, which could accommodate a small army of yogis. Evenings watching the light of dusk nuzzle the Aegean Sea, and brush the island of Telendos that rises up from its waters.

Life was peachy, and it got even better when my ankle was well enough to climb again. One of the chief appeals of Kalymnos are the caves, which offer incredibly overhanging, 3D climbing on mazes of tufa-blobs and free-hanging stalactites. Such is the angle that falling meant swinging into nothing but harmless air—perfect if you’re in ankle-recovery mode.

Climbing such formations is not something that any climbing in New Zealand really prepares you for. Sometimes it’s a single, long feature that must be pinched. Sometimes there are two tufas, and a combination of side-pulling, drop-kneeing and stemming is in order. Other times you seem like you simply cannot hold yourself up any longer, only to find there is a hanging feature behind you that you can thrust a foot, butt cheek or elbow onto and rest.

The Grande Grotta is famous for its routes through the featured roof of the cave. Most are endurance climbs, and if you find inventive ways to wrap yourself around a stalactite, recovery is never too far away. I jumped on Priapos (27 at the time, but since downgraded), an ultra classic named for a sit-down rest about two-thirds of the way up on a tufa-throne with a phallic knob. (Priapos was the Greek God of constant erection.) It’s a typically glorious Grotta climb, starting out steeply to a rest—if you can wrap your legs around a glob of limestone—and then through a bouldery crux that is V2 if you’re tall, and V4 if you’re not.

If you get to the sit-down erection rest, you can have a nap until the blood-flow through your forearms returns to normal. The 40m-route culminates with some tricky manoeuvres to the chains, and the lower off is easy with a 70m rope, such is the severity of the route’s overhang. Topping out feels like the climax of a journey befitting any of the Greek legends, an arduous voyage in which you’ve grown a beard, been betrayed and redeemed, and finally entered the glory of the afterlife to a chorus of triumphant singing.

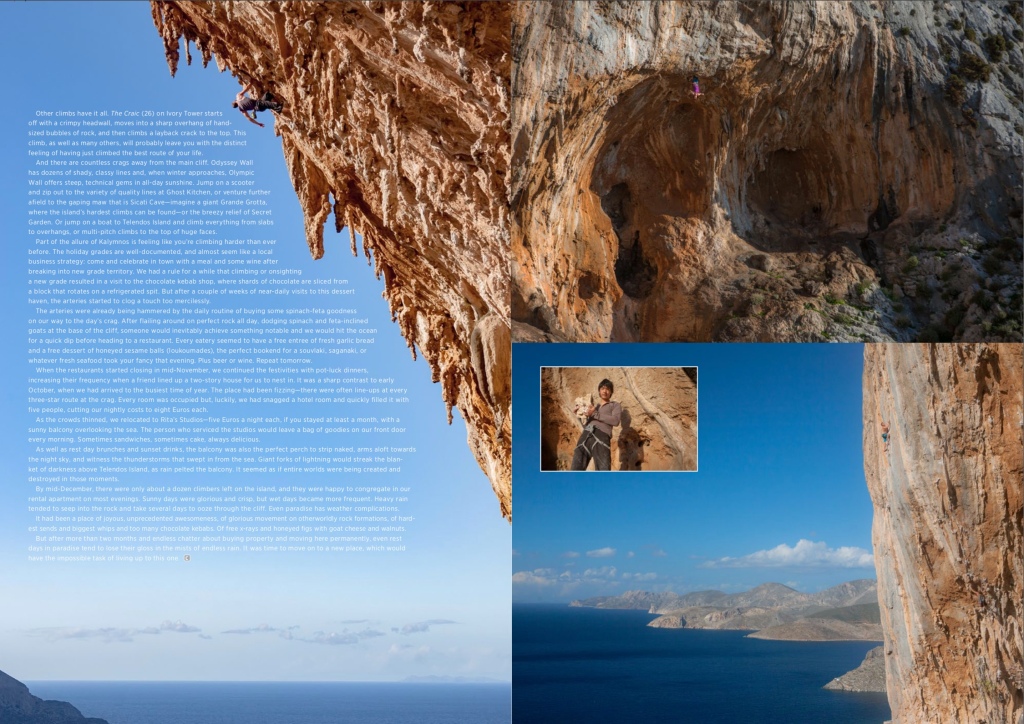

Kalymnos, however, is far more than just the Grande Grotta. Not all limestone is created equal, and Kalymnos limestone is imbued with gold, giving it a particularly deified radiance. There are literally all manner of climbs at all grades— up to 3400 routes, from beginner level to grade 35. It is no exaggeration to say that if you could create your own sport-climbing paradise, Kalymnos would probably not be far from what you would imagine.

Italian Andrea Di Bari must have had a brain-explosion when he came to Kalymnos and gazed up at the rock in 1996, a time when the island’s tourism industry was running mainly on people who liked the sea, and strange sea sponges. Andrea returned the next year and bolted dozens of routes. More recently, The North Face and Petzl have sponsored festivals that have seen harder routes established for the likes of Alex Megos and Sasha Diguilian to play on.

The cliff line above the small, climber-centric township of Masouri, on the west coast, seems endless. There are dozens of crags in a line, offering not only the tufa-blessed lines that Kalymnos is famous for, but technical test-pieces, balancy slabs, and pocket-filled faces.

There’s Jurassic Park, the steep climbs at the northern end of the cliff where most people fear to venture, given the 45-minutes walk(!)—which is also where I happened to injure my ankle. There are two walls of differing angles of overhang. The steeper wall is such that you can happily—or unhappily—skip the last bolt and charge for the anchor, knowing that if you blow it, nothing but 20m of air awaits you in the softest of catches.

The tufa lines of Spartacus Wall are begging to be knee-barred. Spartan Wall and Kalydna offer routes in the realm of the vertical and technical. Iannis has shorter, punchier challenges, while Panorama Wall has longer epics that include climbs like Super Carpe Diem (26), a sublime line where you must wrestle a single tufa that tests the limits of your endurance, before arriving at a hands-free rest on a limestone couch.

Other climbs have it all. The Craic (26) on Ivory Tower starts off with a crimpy headwall, moves into a sharp overhang of hand-sized bubbles of rock, and then climbs a layback crack to the top. This climb, as well as many others, will probably leave you with the distinct feeling of having just climbed the best route of your life.

And there are countless crags away from the main cliff. Odyssey Wall has dozens of shady, classy lines and, when winter approaches, Olympic Wall offers steep, technical gems in all-day sunshine. Jump on a scooter and zip out to the variety of quality lines at Ghost Kitchen, or venture further afield to the gaping maw that is Sicati Cave—imagine a giant Grande Grotta, where the island’s hardest climbs can be found—or the breezy relief of Secret Garden. Or jump on a boat to Telendos Island and climb everything from slabs to overhangs, or multi-pitch climbs to the top of huge faces.

Part of the allure of Kalymnos is feeling like you’re climbing harder than ever before. The holiday grades are well-documented, and almost seem like a local business strategy: come and celebrate in town with a meal and some wine after breaking into new grade territory. We had a rule for a while that climbing or onsighting a new grade resulted in a visit to the chocolate kebab shop, where shards of chocolate are sliced from a block that rotates on a refrigerated spit. But after a couple of weeks of near-daily visits to this dessert haven, the arteries started to clog a touch too mercilessly.

The arteries were already being hammered by the daily routine of buying some spinach-feta goodness on our way to the day’s crag. After flailing around on perfect rock all day, dodging spinach and feta-inclined goats at the base of the cliff, someone would inevitably achieve something notable and we would hit the ocean for a quick dip before heading to a restaurant. Every eatery seemed to have a free entree of fresh garlic bread and a free dessert of honeyed sesame balls (loukoumades), the perfect bookend for a souvlaki, saganaki, or whatever fresh seafood took your fancy that evening. Plus beer or wine. Repeat tomorrow.

When the restaurants started closing in mid-November, we continued the festivities with pot-luck dinners, increasing their frequency when a friend lined up a two-story house for us to nest in. It was a sharp contrast to early October, when we had arrived to the busiest time of year. The place had been fizzing—there were often line-ups at every three-star route at the crag. Every room was occupied but, luckily, we had snagged a hotel room and quickly filled it with five people, cutting our nightly costs to 8 Euros each.

As the crowds thinned, we relocated to Rita’s Studios—5 Euros a night each, if you stayed at least a month, with a sunny balcony overlooking the sea. The person who serviced the studios would leave a bag of goodies on our front door every morning. Sometimes sandwiches, sometimes cake, always delicious.

As well as rest day brunches and sunset drinks, the balcony was also the perfect perch to strip naked, arms aloft towards the night sky, and witness the thunderstorms that swept in from the sea. Giant forks of lightning would streak the blanket of darkness above Telendos Island, as rain pelted the balcony. It seemed as if entire worlds were being created and destroyed in those moments.

By mid-December, there were only about a dozen climbers left on the island, and they were happy to congregate in our rental apartment on most evenings. Sunny days were glorious and crisp, but wet days became more frequent. Heavy rain tended to seep into the rock and take several days to ooze through the cliff. Even paradise has weather complications.

It had been a place of joyous, unprecedented awesomeness, of glorious movement on otherworldly rock formations, of hardest sends and biggest whips and too many chocolate kebabs. Of free x-rays and honeyed figs with goat cheese and walnuts.

But after more than two months and endless chatter about buying property and moving here permanently, even rest days in paradise tend to lose their gloss in the mists of endless rain. It was time to move on to a new place, which would have the impossible task of living up to this one.